The Present Tense of Craft

Why You Matter More Than You Think

Craft does not survive on memory alone.

It does not remain alive simply because something was once beautiful, rare, or historically significant. Craft exists only in the present, because someone, today, chooses to believe in it, engage with it, and take responsibility for its continuation.

At Parvai, through years of working intimately with artists, artisans, and patrons, we have come to understand that craft, like all forms of creativity deeply embedded in human emotion, culture, and environment, is inseparable from its present conditions. It is shaped not only by inherited knowledge, but by the physical body of the maker, the environment they inhabit, the economy they navigate, and the mental and emotional bandwidth required to continue creating. Craft does not exist in abstraction; it exists within lived realities.

While we hold deep reverence for the past and for the extraordinary works that history has left behind, we have come to realise that excessive focus on legacy alone can be misleading. The present cannot be measured against another time period, nor can it be judged by historical abundance or patronage systems that no longer exist. The present must be understood on its own terms, within its constraints, its vulnerabilities, and its possibilities. What is made today deserves to be seen not as a lesser version of the past, but as an honest expression of the circumstances in which it was created.

Over the last decade, we have had the rare privilege of engaging in sustained dialogue with a small but deeply committed community of patrons. These conversations have never revolved solely around products or purchases, but around perspective, how craft fits into one’s life, what it truly takes to sustain it, and how patronage can move beyond transaction into participation. Patrons who chose to engage with craft in this way have experienced something far more enduring than ownership: clarity about process, intimacy with labour, and a sense of shared responsibility within a living ecosystem.

This ecosystem is not built on charity or rescue narratives. It is built on dignity. No one is saving another here. Instead, artisans and patrons sustain each other through belief, fairness, and mutual respect. Each decision, to commission, to wait, to pay fairly, to value depth over speed, directly shapes what is possible for craft in the present.

Yet, in today’s cultural and commercial landscape, craft is increasingly surrounded by powerful language: vintage, revival, recreation, heritage, one-of-a-kind. While these words are evocative, they often romanticise craft while distancing us from its lived reality. They allow us to admire outcomes without engaging with conditions. Beyond these terms lies the true heart of craft, not something frozen in time, but something that longs to be supported, challenged, and allowed to flourish now. What fascinates us is not design alone. It is the environment that allowed a design to come into being at all.

We constantly ask ourselves: what must have gone right, for the body, the mind, the economy, and the patron, for something this beautiful to exist? History may tell stories of brilliance, conflict, appropriation, and ownership, but at Parvai we have come to understand that craft belongs to humankind as a whole. It arises from the same human impulse toward creation, ingenuity, and beauty that unites us all. And with that understanding comes responsibility. Craft does not disappear because knowledge is lost. It disappears when the present no longer supports it.

Handcraft offers no guarantees, no assured future batches, no promises of repetition. Its survival depends entirely on current conditions: the physical and mental endurance of artisans, the respect accorded to their labour, and the presence of patrons willing to stand with process rather than spectacle. Pricing, production, and even what can be offered at any given moment are rooted firmly in now. This is why patronage matters more than ever, not as consumption, but as conscious participation.

To place this perspective in clearer context, we would like to look at two techniques that are widely spoken about today, terms that are familiar, frequently used, and often admired, but rarely examined deeply. Korvai and Adai are among the most popular references in conversations around high-quality South Indian weaving, and most people have heard of them, if not owned or experienced them. By looking closely at what these two techniques truly involve, beyond their names, beyond their visual appeal, we hope to explain what we mean when we speak about the present conditions of craft, the role of the artisan, and, most importantly, the role of the patron in allowing such work to exist at all.

Why Korvai Is Rare And Why That Rarity Is Not Accidental

Korvai is often described as rare.

But rarity is rarely questioned.

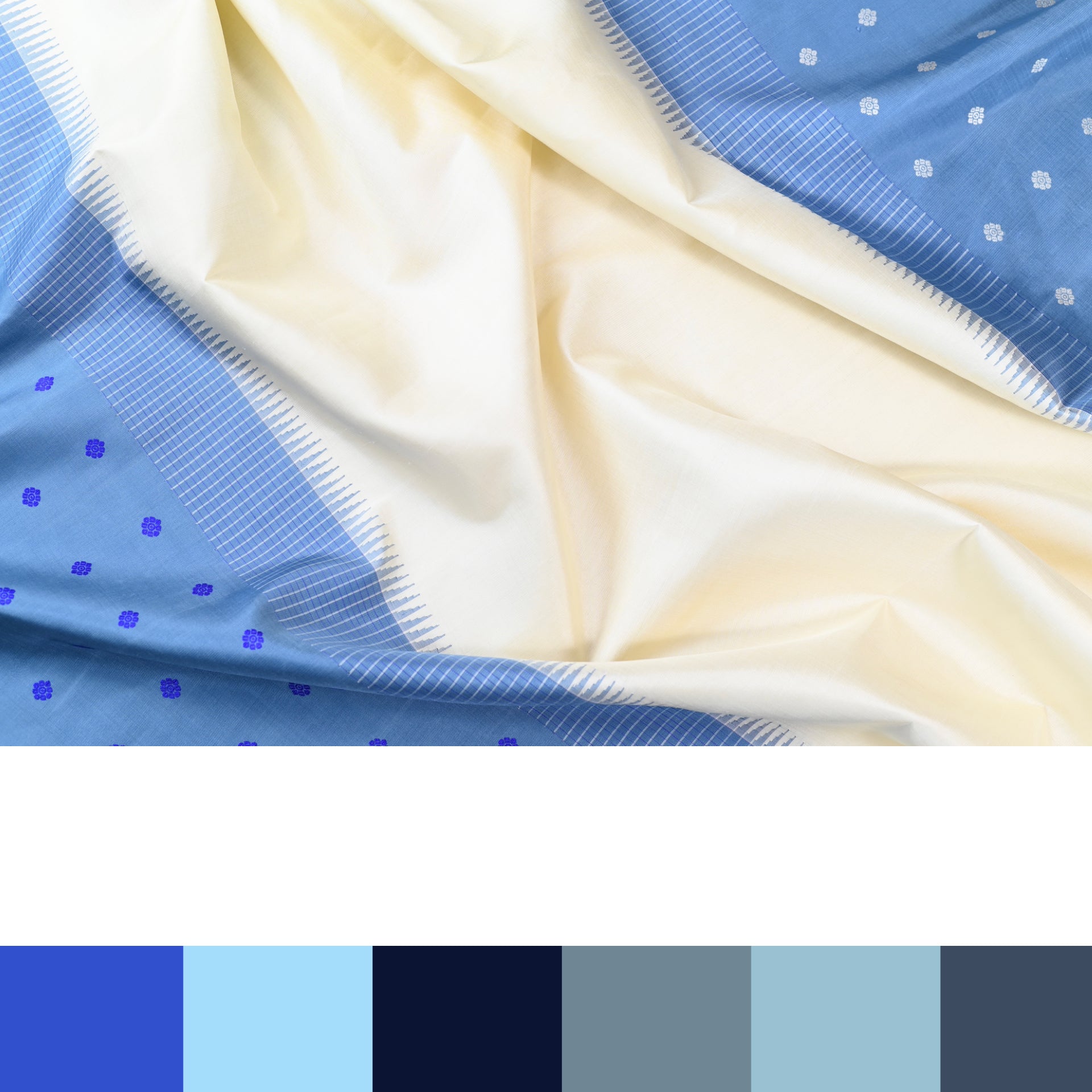

A handcrafted Korvai sari, woven on a traditional three-shuttle loom, especially in Kanchipuram, is among the most labour-intensive textile practices still in existence. Its rarity is not romantic. It is structural, physical, economic, and deeply human.

First: the body.

The Kanchipuram Sari demands one of the highest warp densities in handloom weaving. The thickness of silk yarn, the sheer number of ends on the warp and weft, and the constant handling of multiple shuttles require extraordinary physical strength. This is not passive labour. It is strenuous, repetitive, and unforgiving. In today’s world, marked by lifestyle illness, malnutrition, environmental stress, and reduced physical stamina, the number of bodies capable of sustaining this work has sharply declined. This is not a loss of skill; it is a loss of physical capacity.

Second: the erosion of respect for labour.

The time and effort Korvai demands are rarely acknowledged or compensated fairly. When modified, assisted, or electronic looms can produce Korvai-like saris with fewer yarns, reduced weight, and far less physical strain, they naturally dominate the market. Output becomes the measure of success. Producing more, even at lower quality, feels economically safer. In such a system, choosing a slower, heavier, uncompromising process appears irrational.

Third: the absence of a quality-driven patron culture.

High quality cannot survive in isolation. It cannot exist only in saris; it must be part of a larger way of living. Historically, India thrived because quality permeated daily life. When a market is ill-informed or consciously unwilling to invest in such depth, the final thread of motivation for the weaver disappears.

This is what makes true Korvai rare, not the disappearance of knowledge, but the disappearance of conditions that allow it to exist with dignity. And yet, everything changes when even a small group of patrons believes.

In projects like Amudha, a sister loom producing close to a thousand two hundred finely executed buttas in uncompromising quality takes around 70 days per sari. A visually similar sari, produced on assisted or power looms, can be made nearly ten times faster. But quantity was never the point. The point was always what kind of labour, what kind of life, and what kind of dignity we choose to sustain.

Korvai does not disappear because it is impossible. It disappears when the present no longer supports it.

Adai: The Art of Extra-Weft Textile Ornamentation

Adai weaving, an advanced form of extra-weft ornamentation, has a long history within South Indian handloom traditions, particularly in silk-weaving centres such as Kanchipuram. Historically, Adai was developed as a means of creating complex, symbolic motifs directly within the woven structure, long before the advent of mechanised patterning systems. These motifs often carried cultural, ritual, and aesthetic significance, and the technique evolved in response to environments where time, skill, and sustained patronage allowed such labour-intensive practices to flourish. Adai was never intended for speed or scale; it belonged to a weaving culture where mastery, patience, and continuity were valued over volume.

In traditional Adai work, motifs are not printed, embroidered, or mechanically inserted; they are built into the fabric itself through supplementary weft insertions. A system of hand-knotted pattern threads, often referred to as Adai cords, suspends and activates selected warp threads, holding the design within a living mesh. Multiple weft bobbins must then move in exact coordination with this mechanism, guided entirely by the weaver’s hand, memory, and judgement.

An Adai sari is therefore not merely about visual richness. It is about structural intelligence and sustained concentration. With every added motif, complexity multiplies: density increases, rhythm slows, and the cognitive load on the weaver intensifies. The weaver is constantly counting, aligning, recalling sequences, correcting tension, and maintaining consistency across the entire length of the sari. A single miscalculation can mean undoing days of work. The margin for error is extremely narrow.

This work demands far more than physical endurance. It requires exceptional mental stamina, spatial memory, and emotional resilience, capacities that are rarely acknowledged in pricing, timelines, or appreciation. Unlike simpler woven patterns, Adai does not allow for autopilot. Every inch requires presence.

Assisted looms reduce this burden by mechanising parts of the patterning process. Power looms remove it almost entirely, separating the weaver from the cognitive labour that historically defined Adai. As these alternatives dominate the market, the logic of survival quietly pushes artisans away from depth toward speed. Producing more begins to feel safer than producing better.

What disappears, then, is not technique. What disappears is motivation.

When there is no patron willing to wait, to pay fairly, and to understand what density truly costs—in time, concentration, and human effort, craft adapts downward. Not because artisans are incapable, but because they are human. This is where patrons become the single most decisive force in determining whether Adai survives as a living, thinking craft, or remains only a word we admire from a distance.

The Numbers We Cannot Ignore

India’s handloom and handicraft ecosystem supports over 6.4 million artisans, with more than 35 lakh handloom workers recorded in the most recent census. Nearly 72% are women, making craft one of the largest livelihood ecosystems for women in rural India.

And yet, studies estimate that up to 30% of traditional artisans have abandoned their craft, driven by poor remuneration, lack of informed patronage, and unsustainable working conditions. Faster, assisted, and power-loom alternatives dominate markets, rewarding speed over endurance.

A true Korvai or heavy Adai sari Like Parvai's Amudha may take 60–75 days on a traditional loom. A visually similar product can be produced up to ten times faster on assisted systems. Productivity has replaced patience. Quantity has replaced depth.

Craft does not disappear because it lacks history. It disappears when the present stops valuing it.

The Patron Is the Rarest Resource

When the journey toward Parvai began, words like rare, expensive, hard, and one-of-a-kind surrounded high-quality craft. Over time, one truth became clear: it is not people who have disappeared. It is not wisdom. What has become rare is the patron.

We may not have large numbers by conventional retail standards, but the depth of impact created by a single patron is immense. In many instances, the commitment of one patron has sustained the livelihoods, dignity, and aspirations of more than five families, not merely enabling survival, but enabling progress.

With a patron community of fewer than a hundred, we have built a living ecosystem, from museum-worthy textiles to everyday luxury, experienced deeply by everyone involved.

Living Forward, Not Looking Back

As we forge our humble path forward, together with our artisans and patrons, we choose to live in the present. We are not interested in spectacle or over-glorification. We are interested in discernment, inviting craft into our lives without excess, without overcrowding, and with intention.

In doing so, patrons become quiet evangelists, carrying forward the values of sustainability, dignity, and excellence into their own communities. This is how messages travel. This is how quality survives.

To be present.

To ask questions.

To participate rather than consume.

This is how craft of worth remains alive. And this is the truth we leave with you:

Every craft you experience today exists because someone chose to be present.